I have a YouTube channel where I uploaded dozens of video lectures I created, covering Chinese philosophy from Confucius through Xi Jinping. YouTube (which is owned by Google) deleted the channel without warning, and lied to me that all my content had been deleted without backup. Fortunately for me, I have thousands of Twitter followers, so I was able to apply social media pressure which led YouTube to restore my (allegedly unrecoverable) media. My story illustrates that YouTube’s copyright enforcement system is broken and unjust. This is not just an isolated problem, but illustrates a general feature of contemporary life, in which large institutions benefit us in many ways, but are increasingly unresponsive to our concerns.

Okay, now let’s take it from the top. Most of the content on my channel was created by me, or is playlists of material on other channels relevant to my teaching. However, because I teach about “Orientalism,” I also uploaded a series of clips from a 1934 film, “Java Head,” which is historically important because it is an early film about an interracial marriage, and stars the first great Chinese-American actress, Anna May Wong, who has recently been featured on a quarter. (In a later post, I’ll discuss the original novel the film is based on, and why I think we need a remake of the film, with a different ending.)

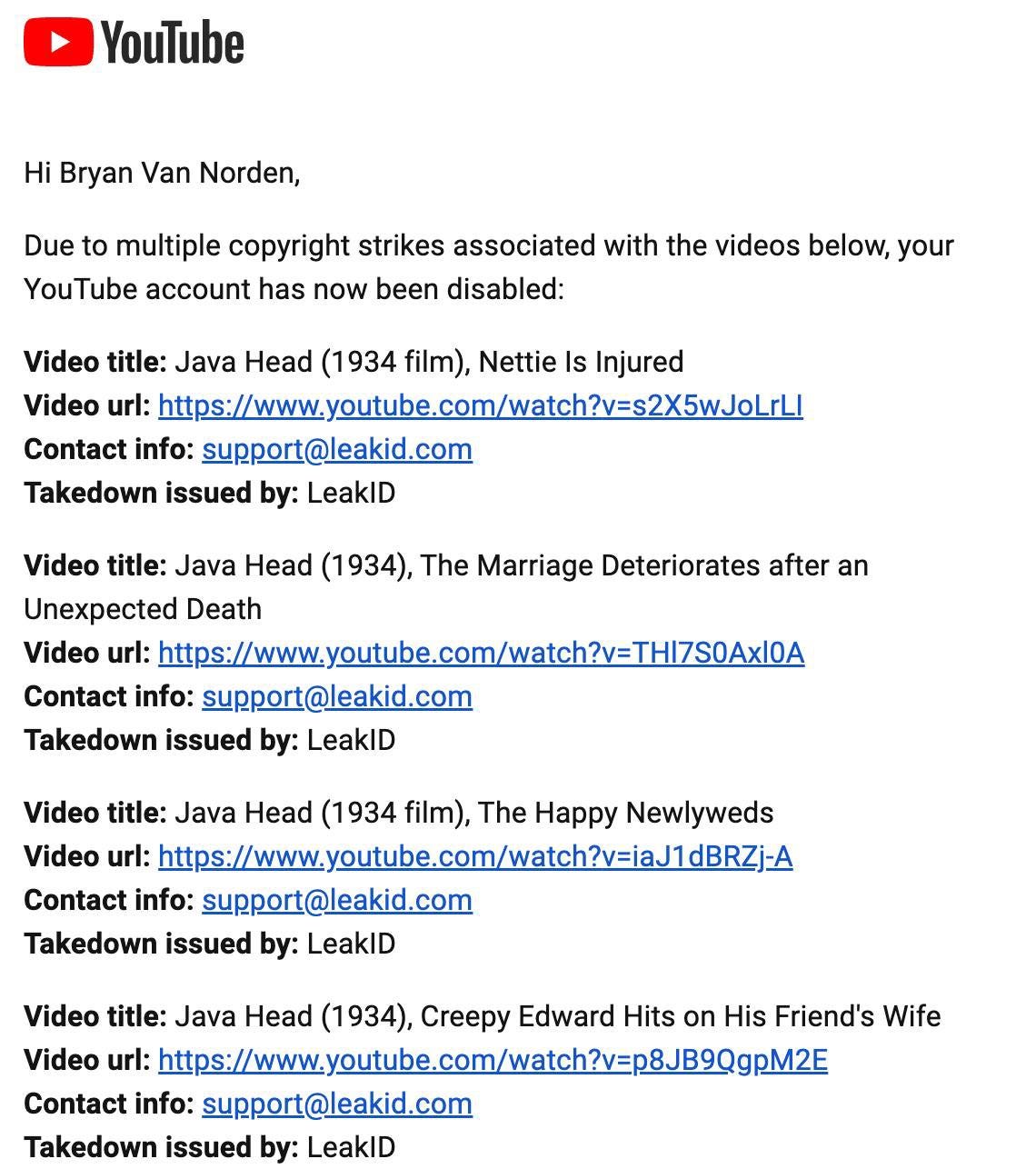

“Java Head” is almost impossible to find, either online or on DVD, but I found the video hosted on a free Facebook page, so I decided to make some curated clips available for my students. I uploaded the clips (from the free Facebook page, which is still up) last year (definitely prior to 9 July 2021), where they stayed without any warnings from YouTube about potential problems. Then, out of the blue, on 6 June 2022, I was informed that an external bot owned by a company called “LeakID” found the clips and made a copyright claim against them to YouTube.

YouTube’s policy is that an account is disabled after three “copyright strikes” against them. When you get one copyright strike, you are given a warning. However, because I had more than three clips from “Java Head,” I immediately got more than three strikes, so without warning to me an internal YouTube bot disabled my channel. To protest a copyright strike, you have to log into your channel, but of course I cannot do that because they deleted my channel. I did find email addresses to appeal directly to YouTube and Google: YouTube said I did not have a legitimate response to the copyright strikes, and Google said they could not help me because my account had been permanently deleted and could not be restored.

On my YouTube channel are my Chinese Philosophy Class Lectures covering Confucians like Mengzi, Daoists like Zhuangzi, the Classic of Changes (I Ching), the differences between Mahayana and Theravada Buddhism, East Asian Buddhism including Huayan and Zen, Neo-Confucianism, Chinese feminism, and Chinese responses to modernity, including the May Fourth Movement, Communism, and recent trends like Xi Jinping’s Confucian socialism. The videos are arranged in historical order with cross-reference cards, and have been used and praised by people all over the world. They were all deleted because one careless bot told another careless bot to do so.

When I got the first email from YouTube, I immediately clicked the link to submit a “counter notification.” Part of that page says I have to log in to my “YouTube Studio.” Of course, I could not do that, because I was locked out of my account. (Catch-22!) However, I found the direct email address for copyright issues and sent my request for resolution (with a typo in the first line; sigh):

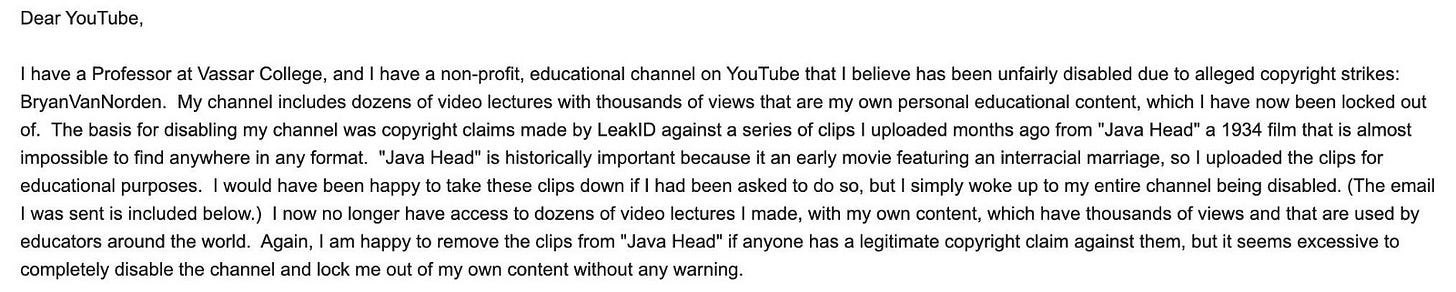

If I had to do this part over, I would have used more specific buzzwords, like “fair use for education purposes.” However, I feel that this email made the situation fairly clear: I am an educator, my channel is non-profit, most of the content on my channel is my own creation, I had reason to believe that the clips were in the public domain, I was uploading them for education and historical purposes, and I received no warning before locking me out of my channel and (for all I knew) deleting my content. I quickly got a reply from YouTube stating “it’s unclear to us whether you have a valid reason for filing a counter notification…”

At this point, I began to suspect that YouTube treats an account “disable” differently from a “copyright strike.” This suspicion was confirmed (I think?) by an email from YouTube that does not identify what it is responding to, but informs me that “if your channel has been removed due to copyright infringement, we are unable to process your appeal.”

So after some more internet sleuthing I found a link to appeal a YouTube ban. This page informed me that I need to know my “Channel ID” to successfully appeal the ban. HOWEVER, a Channel ID is not intuitive, and there is no direct way to access your Channel ID after you are locked out of your account. (Another Catch-22!) I guessed that my Channel ID was “BryanVanNorden” since that is my display name. I was wrong. My Channel ID, I now know, is a random 24-symbol-long alphanumeric string.

But I filled out the form as best I could, and I soon got an email back from Google, informing me that: “The email address you inquired about is not associated with an active Google Account. If this email address was previously associated with a Google Account it has been deleted and cannot be recovered.”

Now, as I noted above, I did not know my actual Channel ID, and I was aware I might have gotten it wrong, but the fact that they referred to the email address associated with my account made me think that they actually had checked the status of the correct account, and that all my content was now lost.

At this point, I decided to vent on my social media. Fortunately for me, when this all started, I had over 9K Twitter followers and 2.6K Facebook friends. Within 24 hours on Twitter, my post had almost 7K likes, over 1.5K retweets, and over 300 quote tweets — almost all sympathetic and furious on my behalf. (I got a couple less sympathetic replies, to the tunes of “grandpa doesn’t know about backing up files” — more about this below — and “this is what pronouns in your bio leads to.”)

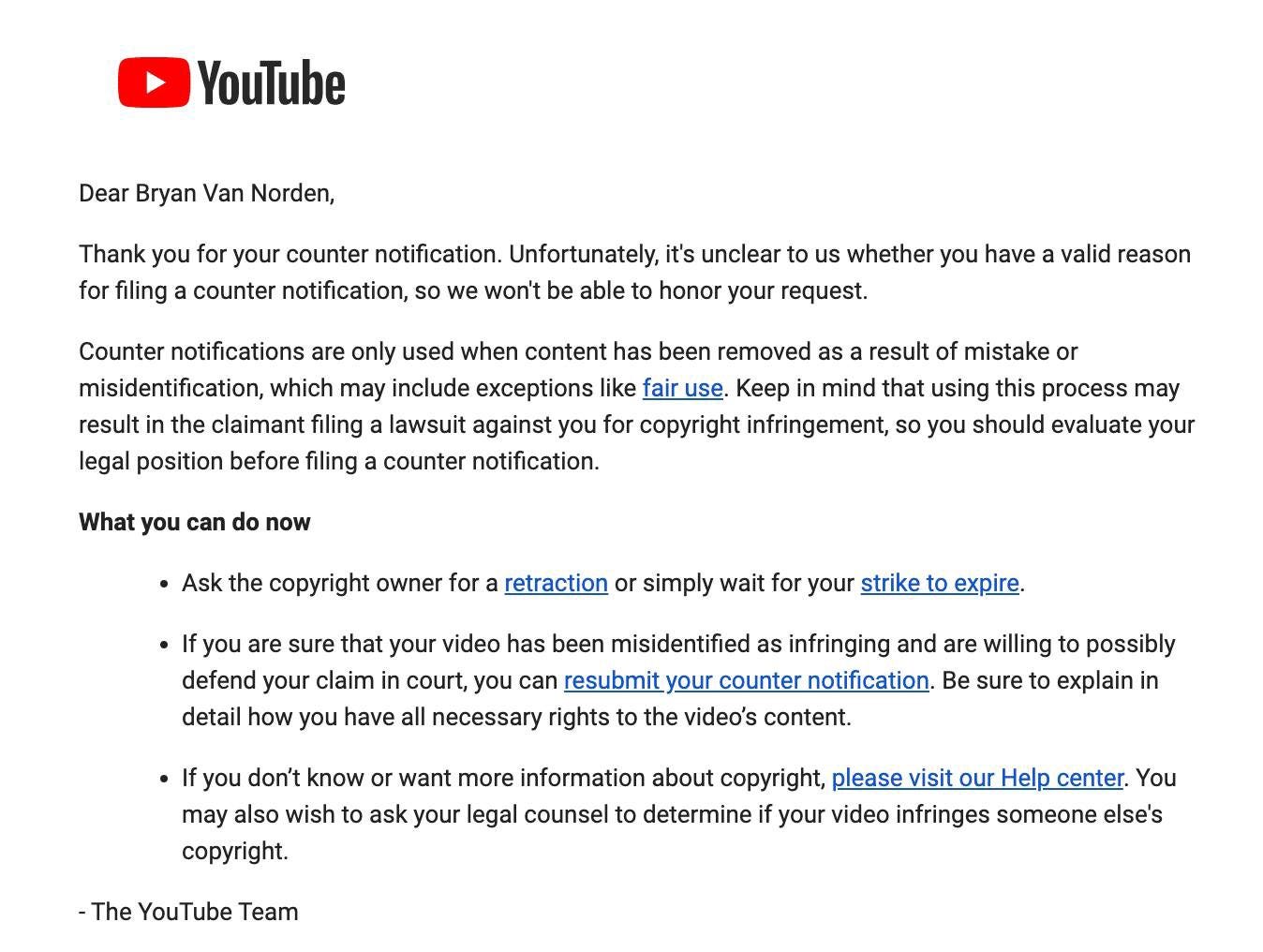

Coincidentally (I’m sure!), that evening I got the first email from YouTube that appeared to be from an actual human being, “Tony,” who essentially invited me to resubmit my counter notification:

My wife is an attorney, so she also did some legal research for me. It appears that “Java Head” is actually still under copyright. However, a random Twitter user also informed me: “The copyright office has records for the movie, but no record of renewal by 1962, which the rights holder would have needed to do for subsequent records to be valid. However, their digitized records are very spotty and it may have been renewed and just not digitized.” Another random Tweet informed me that LeakID, the company that made the copyright claim against me, has a very dubious record.

In any case, from the fact that “Tony” was now involved, it appeared that YouTube/Google was looking for a face-saving way out of what was turning into a public relations nightmare for them. It was getting late in the day by the time my wife and I had talked this through and agreed on a strategy for my response to Tony, so we decided I would get some sleep and write my response to Tony the next morning.

When I got up early the next morning (9 June 2022), I reviewed my latest tweets over coffee, and someone had Tweeted that my channel was back up. I checked and to my astonishment it was true: my YouTube account was restored, with all the old content intact, except for the videos from “Java Head.” I checked my emails and, for each of the clips from “Java Head” that I uploaded, there were TWO emails from YouTube, with conflicting accounts of the status of the clips: one saying that the copyright claim was released, and one saying that a copyright owner has claimed the content, but this is not a copyright strike:

After consulting with my “consigliere” (a joke my Italian-American attorney wife enjoys), I wrote a carefully worded letter back to my pal “Tony,” confirming that, while I admitted no wrongdoing, I took the matter to be resolved, and later that evening Tony agreed that it was resolved:

I then announced on Twitter and Facebook:

So what lessons have I learned from this?

First, why did I not back up my videos so that I was not at the mercy of YouTube? Good question, but I believed (mistakenly) that YouTube was the safest place to store my videos. I am old enough to remember how many files I have lost (in various media) because they were on what are now outdated media. (Remember zip drives, which were big for about a year?) I figured YouTube is not going away any time soon, so it is the most stable, and safest place to store large video files. (HA!)

However, lesson learned! As soon as I got access to my videos again, I downloaded copies to my laptop and to my Dropbox. I also contacted the school where I teach, and found out that we have a Panopto server I did not know about. I’m sure my school told me about this at some point, but part of the problem we have in modern society is that we are given much more information than we can effectively process, but we are often held accountable for not knowing pieces of this information.

The second lesson from all of this is that copyright protection on YouTube is, to put is succinctly, “broke.”

Dozens of hours of uniquely valuable educational material were threatened with extinction because one careless bot told another careless bot to do so.

It was almost impossible for me to fix this problem, because the directions I was given for appeal required that I log into a channel that no longer existed, and cite the Channel ID that could only be found by (you guessed it) logging into the non-existent account. When I managed to provide the information that should exonerate my account, I was told (falsely!) that my videos could not be restored in any case.

It is only because I have a social media following that created a public relations nightmare that I was able to get “Tony” involved. In fact, it turns out that “Tony” didn’t need a reply from me. When it was clear the Tweetstorm in my support was not abating, someone somewhere (“Tony”? “Toucan Sam”? “The Men in Black”?) decided that, “you know what, the copyright claim is released. Oh, wait, you know what, though? It’s not released, those videos are blocked, but you have no copyright strikes. How about that?”

Third, as both Aristotle and Confucius noted, humans are communal animals. (Forgive me waxing philosophical — but I am a philosopher.) “Humans are communal animals” means that humans only really flourish with the help of other humans in communities. Consequently, we have obligations to other humans. Large corporations like YouTube and Google provide valuable services and transform our lives in many ways, often positively. I am delighted that my video lectures on Chinese philosophy can now reach people all over the word. However, corporations and the individuals who run them benefit from us too. I don’t only mean that corporations benefit from the content creators, but also from the grade school instructors who teach children to read who later go on to work for YouTube/Google, the people who did the research that led to modern computers (from Leibniz and Babbage and Lovelace to Alan Turing and Grace Murray Hopper and on to contemporary researchers), and the people who staff the garbage trucks that clear away the refuse produced in the YouTube/Google offices, etc. etc.

Big corporations and the very wealthy need to remember that we’re all in this together, we all owe each other, and as another great philosopher put it, “nobody wins unless everybody wins.” More specifically, corporations like YouTube/Google are entitled to profit from changing our lives in positive ways, but with the right to profit comes a responsibility to benefit. The practices of YouTube regarding copyright management are increasingly arbitrary and failing to act for the greater good.

Bryan W. Van Norden is James Monroe Taylor Chair in Philosophy at Vassar College, and the author of ten books, including Taking Back Philosophy: A Multicultural Manifesto. Opinions expressed here are his own and may not reflect those of Vassar College.

We in the World of Wong are beginning to believe in The Curse of Java Head.

“Princess” Taou Yuen was right.