[Below is the slightly revised text of my remarks at “Thousand-petal Flower: Lin Huiyin as a Guardian of Cultural Heritage with Roots in Fuzhou,” an event held in Philadelphia, PA, on 2 May 2024, hosted by the Fujian Art Museum.]

For many reasons, it is a great honor for me to talk today about Lín Huīyīn 林徽因. First, Lín and I are both graduates of the University of Pennsylvania. I graduated with a B.A. in philosophy in 1985, and Lín graduated from Penn with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 1927. Lín earned, and certainly deserved, a Bachelor of Architecture degree, but she was originally denied the degree because women were not allowed to pursue degrees at the school of architecture at that time. I am delighted that Penn will be redressing this injustice by conferring the degree upon her later this month.

My second reason for being especially excited to talk about Lín Huīyīn is that I am a researcher and teacher of China’s intellectual history, and Lín is a major figure not only as a poet and a historian of architecture, but she is also (along with her husband Liáng Sīchéng 梁思成) one of the founders of the movement to preserve traditional Chinese architecture. The third reason that I am especially excited to talk about Lín Huīyīn is that her life illustrates the productive ways in which Chinese and American scholars, and Chinese and American scholarship, can learn from and benefit one another.

Lín was born in 1904, near the end of the Qing dynasty, in Hángzhōu 杭州 in Zhèjiāng Province 浙江省, but her family’s ancestral home is Mǐnhòu County 闽侯县 in Fújiàn Province 福建省. Consequently, it is dulce et decorum, as they say in Latin, “sweet and becoming,” that our event today is sponsored by the Fujian Art Museum (福建省艺术馆). I am sure that Lín would be deeply honored that the Fujian Art Museum has sponsored this event and sent a delegation that has travelled all the way from China to celebrate the life and accomplishments of Lín.

I feel a little silly as an American lecturing a largely Chinese audience about the famous Lín Huīyīn, but please allow me to share with you some of what I as an American find most fascinating about her life. In the Qing dynasty, when Lín was born, women did not normally receive advanced education; many were illiterate. However, Lin was born into a progressive family that was influenced by the New Culture and May Fourth Movements. As a child, she received an education that emphasized the best of both Chinese and Western education, then went abroad and enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania in 1924. In 1928, after earning her BFA, Lín married fellow Penn architecture student Liáng Sīchéng. Liáng had an impressive background; he was the son of the famed Chinese reformer Liáng Qǐchāo 梁启超. Lín and Liáng complemented each other, like yīn 阴 and yáng 阳. Lín was glamorous and vivacious. From her photographs, Lín reminds me of the great American actress Katharine Hepburn. Hepburn was born just a few years after Lín, and they both look powerful yet feminine in stylish pantsuits.

In addition to being an architect, Lín also wrote poetry, fiction, criticism and drama. The Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore once composed a poem in praise of Lín: “The blue of the sky / fell in love with the green of the earth. / The breeze between them sighs, ‘Alas!’” In contrast, her husband Liáng was, by all accounts, a quiet, scholarly architect and teacher. But something was magical about them as a couple. Liáng and Lín have even been compared to another famous artistic couple, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo of Mexico.

Regarding their general historical significance, Nancy Steinhardt, professor of East Asian art at the University of Pennsylvania, commented: “Liáng and Lín founded the entire field of Chinese historical architecture. They were the first to actually go out and find these ancient structures. But the importance of their field trips goes beyond that: So many of the temples were later lost—during the war with Japan, the revolutionary civil war and the Communist attacks on tradition like the Cultural Revolution—that their photos and studies are now invaluable documents.” (Incidentally, Professor Steinhardt very much wanted to attend this event, but she happens to be in China at the moment, so she could only send her best wishes.)

After getting married and traveling in Europe for a while, Lín and Liáng returned to China, eventually teaching at Tsinghua University (Qīnghuā dàxué 清华大学). Among the guests at the intellectual salons hosted by Lín were two young American friends, John King Fairbank and his wife, Wilma. John Fairbank would go on to become a founding figure in Sinology in the United States, and an adviser to the U.S. government on Chinese policy from World War II to the 1970s. (The Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University is named after him.) John Fairbank’s wife, Wilma, was an authority on Chinese art in her own right, and played a key role in preserving the work of Lín and Liáng.

In 1934, Lín and Liáng invited John and Wilma Fairbank to join them on a trip to find and document the Guǎngshèng Temple 广胜寺) in Shānxī Province (山西省). After days of avoiding warlords and traveling on roads that rain had turned into almost impassable mud, the two couples finally arrived at the temple at dusk. The monks allowed the Fairbanks and the Liángs to sleep in the temple overnight. In the morning, Lín and Liáng discovered a secret staircase behind a statue of the Buddha and were able to use it to climb to the top of the temple.

Lín and Liáng’s greatest discovery came on another expedition to Shānxī Province, in 1937, when they dated and meticulously cataloged the Fóguāng Sì 佛光寺, or the Temple of Buddha’s Light. This wooden temple was built in 857 A.D., making it the oldest known building in China at the time. (It is now the fourth-oldest known.)

The calls of Lín and Liáng to preserve traditional Chinese architecture were not always appreciated during their own lifetimes. Lín Huīyīn succumbed to a long battle with tuberculosis in 1955. Liáng lived until 1972, but by then much of the beautiful traditional architecture of Beijing had been destroyed. Ironically, even Lín and Liáng’s historical home in Beijing was demolished by developers in 2012.

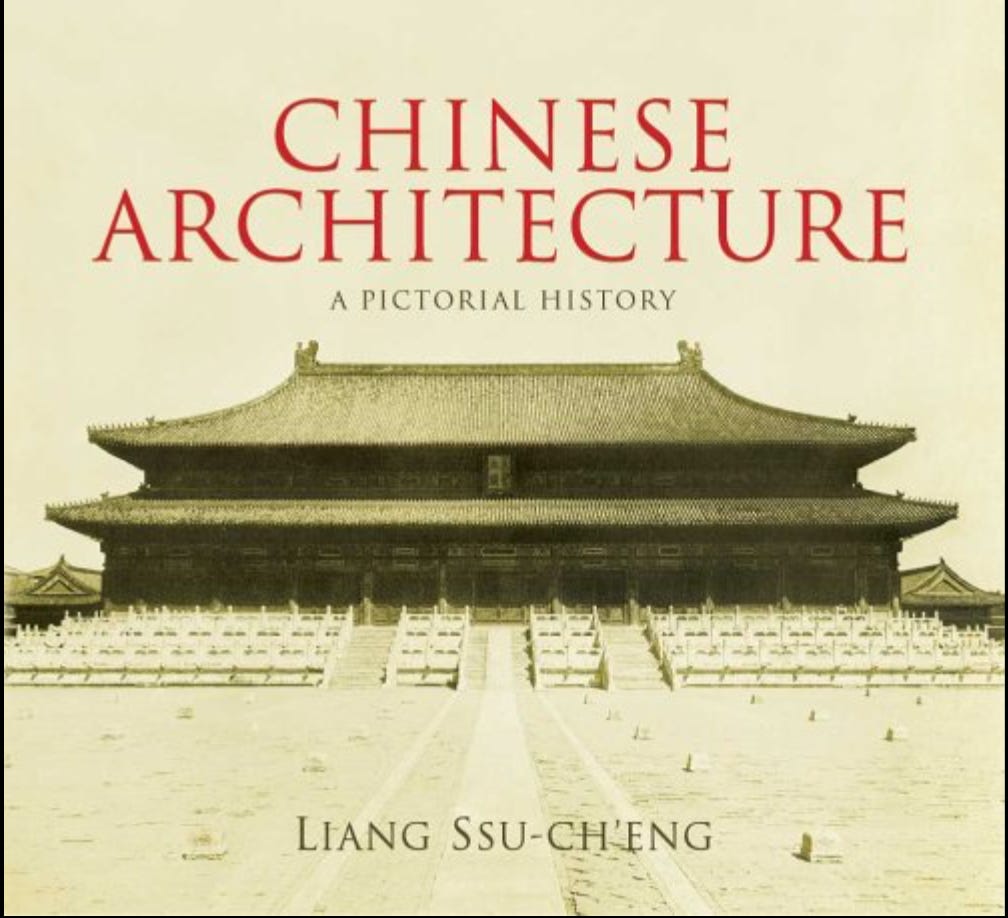

Fortunately, in the 1980s, their old friend John Fairbank managed to track down Lín and Liáng’s drawings and photographs from the 1930s and combined them with a manuscript that Lín and Liáng had been working on during World War II. The posthumously published volume, Chinese Architecture: A Pictorial History, preserved records of many beautiful buildings that no longer exist. (Liáng is listed as the sole author of this book, but there is a consensus that Lín was his uncredited collaborator on much, if not all, of his work.) Wilma Fairbank, for her part, wrote a book about the pair: Liang and Lin: Partners in Exploring China’s Architectural Past, which helped introduce them to a Western audience.

Lín’s niece is the famous Chinese-American architect Maya Lin (Lín Yīng 林璎). Maya Lin is perhaps most famous for designing the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. This monument was controversial when it was first built because it is not a traditional style of memorial, but over the years the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial has become recognized as one of the greatest and most moving works of art in the US. Maya Lin was asked about the significance of her aunt and uncle. She joked: “Since when did historical preservationists get to be so sexy?” More seriously, Maya Lin explained that the pair have “become folk heroes in China for having stood up for preservation, like Jane Jacobs here in New York, and they are celebrities in certain academic circles in the United States. … from an architectural point of view, they are hugely important. If it weren’t for them, we would have no record of so many ancient Chinese styles, which simply disappeared.”

For me, part of what the life of Lín Huīyīn illustrates is how productive cooperation between Chinese and Western scholars and scholarship can be. Figures like Lín Huīyīn, Liáng Sīchéng, Hú Shì 胡适 (Hu Shih), Féng Yǒulán冯友兰 (Feng Yu-lan), Lín Yǔtáng 林语堂, and many others both learned from America, but also taught America a great deal. Although diplomatic relations between China and the US are sometimes strained today, I look forward to a future in which China and the US return to our historic friendship and cooperation.

Thank you!

Sources

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/05/world/asia/in-beijing-razing-of-historic-house-stirs-outrage.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/obituaries/overlooked-lin-huiyin-and-liang-sicheng.html

Wikipedia contributors, "Lin Huiyin," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Lin_Huiyin&oldid=1217826065 (accessed April 30, 2024).