Studying Philosophy Is Useless

Except to Scientists, Businesspeople, Attorneys, Physicians, Clergy, Artists, Influencers, Activists, War Heroes, and Citizens of a Democracy

Among the most the exciting things about attending a college or university is the freedom to study what you want, and the wide range of courses offered. In particular, your college or university experience is probably your only chance to take courses in philosophy. However, many students (and their parents) wonder what benefit there is to taking philosophy courses. Isn’t philosophy just something that dead white guys with long beards in robes used to do before we had TV to entertain us? On the contrary! Studying philosophy — whether majoring in it or just taking one or more philosophy courses — is a legitimate career choice, even from a narrowly vocational perspective. Studying philosophy is also valuable to every citizen of a democracy, and to the maintenance of democracy itself. Moreover, philosophy has made immense contributions to our civilization, especially to the development of science, and by its nature it is impossible for philosophy to ever become obsolete.

1. Philosophy and Getting a Job

Philosophy majors earn more than those with any other humanities degree, and my own students have gone on to success in a variety of different professions, including medicine, Wall Street, teaching, social work, and law enforcement. For those considering a law degree, it is worth knowing that undergraduate philosophy majors on average score higher than any other major on the LSATs (Law School Admission Test). (I have three former students who attended top law schools after majoring in philosophy: one at Columbia Law School, another at NYU Law School, and a third at the University of Michigan Law School.) Philosophy majors also have the highest average score on the GRE Verbal and GRE Analytical Writing (required by many graduate programs), and are among the highest-scoring majors for the GMAT, the business-school admissions test. Perhaps most impressively, philosophy majors have the highest average probability of getting admitted to medical school, better on average than any other major, better than even biology and chemistry majors!

What else do people who majored in philosophy do? A philosophy major can be president of Morgan Stanley (Robert Greenhill), founder and manager of a hedge fund (Don Brownstein), an investor (George Soros and Carl Icahn), CEO of Overstock.com (my former Stanford classmate and philosophy PhD Patrick Byrne), CEO of Time Warner (Gerald Levin), CEO of Hewlett-Packard and Republican presidential candidate (Carly Fiorina), cofounder of PayPal (Peter Thiel), a Supreme Court justice (Stephen Breyer and David Souter), cofounder of Wikipedia (Larry Sanger), mayor of Los Angeles (Richard Riordan), US secretary of education (William Bennett), chair of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (Sheila Bair), political activist (left-wing Stokely Carmichael and right-wing Patrick Buchanan), prime minister of Canada (Paul Martin, Jr.), president of the Czech Republic (Vaclav Havel), a network television journalist (Stone Phillips), a Pulitzer Prize–winning author (Studs Terkel), a Nobel Prize–winning author (Pearl Buck and Bertrand Russell and Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus and Alexander Solzhenitsyn), a Nobel Peace Prize winner (Albert Schweizer and Aung San Suu Kyi), host of an iconic game show (Alex Trebek), a comedian/actor/producer (Ricky Gervais and Chris Hardwick), an Academy Award–winning filmmaker (Ethan Coen), a four-star general in the US army (Jack Keane), a fighter in the French Resistance in World War II (Stephane Hessel), coauthor of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (P. C. Chang and Charles Malik), a martyr to German opposition to Nazism in World War II (Sophie Scholl), pope (John Paul II and Benedict XVI), or a seminal anthropologist (Claude Levi-Strauss and Clifford Geertz)—just to give a few examples.

The practical value of our discipline relates to the fact that philosophy courses typically do particularly well at teaching the “three Rs” of a humanities education: reading, writing, and reasoning. Philosophy is not unique among humanities fields in teaching reading, writing, and reasoning, but philosophy classes typically put a special emphasis on clarity of expression, accuracy of interpretation, and cogency of argumentation that is sometimes lacking in other disciplines.

I certainly wouldn’t say that everyone should major in philosophy (there’s nothing that everyone should major in), but some training in the reading, writing, and reasoning skills that are distinctive of philosophy courses is valuable to majors in a variety of different fields. I know an engineer who, as an undergraduate, fed me the line every humanities professor must have heard at some point: “Why should an engineer be required to take a humanities course instead of taking that one additional engineering course that would help him design a bridge that won’t collapse?!” First, any engineer who is only one course away from designing a bridge that collapses should not be anywhere close to graduation! I expect my bridges to be designed by engineers who are well over the absolute minimum skill level required. More seriously, the fact is that, when you study a technical field, advanced knowledge is constantly changing. You always use the concepts that are taught to you in the basic courses your freshman and maybe your sophomore year. After that, the content of your courses is typically things that will be obsolete a few years after you graduate, or perhaps irrelevant to the particular job you end up in. You are still getting something out of them, but it is simply more practice in “thinking like an engineer” (or a businessperson, or a computer scientist, or whatever). This is certainly valuable. However, whatever sort of career you end up in, if you need a college degree for it, part of your job will be reading challenging texts with understanding and writing clearly and persuasively. If you end up in an advanced management position, your job may also involve understanding and discussing knowledgeably issues involving ethics. How do I know all this? The engineer in question admitted it when I talked to him years later, after he had practical experience in his own profession.

Let us remind ourselves that the distinctive higher education system of the United States—which requires most students to take a liberal arts curriculum and, since World War II, has been increasingly open to people of all social classes—is the envy of the world. No wonder, because the system that makes natural scientists study poetry and philosophy has produced nuclear power, computers, supersonic flight, the polio vaccine, lasers, transistors, oral contraceptives, CDs, the Internet, email, and MRIs, and has put the first people on the moon. Ironically, as liberal arts education in the United States is increasingly under fire, governments in China, India, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea try to re-create in their own countries the liberal arts model that they recognize is one of the keys to US technological and economic dominance.

2. Philosophy and American Democracy

Of course, America is widely admired not just for its scientific achievements, but also for being a pluralistic democracy. Philosophy has had, and I think continues to have, an important influence on American democracy. Thomas Jefferson’s huge personal library became the basis for the Library of Congress, and he was deeply read in philosophy. As a political theorist, Jefferson was very influenced by philosopher John Locke, and Jefferson argued that the best way to combat tyranny is

to illuminate, as far as practicable, the minds of the people at large;… whence it becomes expedient for promoting the public happiness that those persons, whom nature hath endowed with genius and virtue, should be rendered by liberal education worthy to receive, and able to guard the sacred deposit of the rights and liberties of their fellow citizens, and that they should be called to that charge without regard to wealth, birth or other accidental condition or circumstance….

In other words, Jefferson argued that a liberal arts education should be available and affordable for everyone who can benefit from it, regardless of whether they happened to be born into wealth or not. Consequently, the disdain of many contemporary politicians for publicly funded liberal arts education is in opposition to the wisdom of America’s Founding Fathers, and it ignores a significant part of what has made America “exceptional” and a “shining city upon a hill,” among other nations.

Jefferson is not the only US Presidents who was a proud intellectual. Abraham Lincoln boasted of “having studied and nearly mastered” the ancient classic of geometry, Euclid’s Elements, and his Gettysburg Address was modeled on the Funeral Oration of the Athenian statesman Pericles. Teddy Roosevelt was a member of Phi Beta Kappa, the liberal arts honor society, and also a Magna Cum Laude graduate of Harvard. Herbert Hoover spoke Chinese and translated the Renaissance work of metallurgy De Re Metallica out of Latin. Dwight Eisenhower was not only a graduate of West Point and a war hero, but also president of Columbia University. Richard Nixon earned a degree from a liberal arts college before going on to law school. And George H. W. Bush (that’s the father, not the son) was Phi Beta Kappa at Yale.

The political importance of philosophy for a pluralistic democracy can also be understood from a study of recent history. Sir Stuart Hampshire was a leading British philosopher who served in military intelligence during World War II. As part of his assignment in military intelligence, Hampshire participated in the debriefing of Nazi officers, and through these interviews he came to recognize that

below any level of explicit articulation, hatred of the idea of the Jews was tied to hatred of the power of intellect, as opposed to military power, hatred of law courts, of negotiations, of cleverness in argument, of learning and of the domination of learning: and in this way anti-Semitism is tied to hatred of justice itself, which must set a limit to the exercise of power and to domination.… The Nazi fury to destroy had a definite target: the target encompassed reasonableness and legality and the procedures of public discussion, justice for minorities, the protection of the weak, and the protection of human diversity.

One of the most persuasive and moving accounts of the value of philosophy and a liberal arts education was offered by US Admiral James Stockdale. Stockdale was a POW in the Vietnam War. Prior to the war, he had taken a philosophy course at Stanford in which he studied the thought of the Stoic Epictetus. Epictetus teaches that maintaining one’s integrity is more important than anything else, certainly more important than avoiding pain. He also argues that we must learn to accept our fate, and that hatred of our opponents is a trap. Stockdale said that philosophical lessons he learned from Epictetus helped him to survive years of torture with his character intact. Upon his return to the United States, Stockdale was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest award given by the US military, for his courage and leadership as a POW.

Many people seem to think that education should only involve studying authors you agree with. (More accurately, they think you should only study authors they agree with.) However, Stockdale said that it was a great benefit to him that he had taken a course in which he read systematically and charitably the works of Marx and Lenin: “In Hanoi, I understood more about Marxist theory than my interrogator did. I was able to say to that interrogator: ‘That’s not what Lenin said; you’re a deviationist.’ ” Stockdale explained that among the soldiers most vulnerable to being “turned” by their interrogators were those who had never been exposed to criticisms of their own country, and had never gotten the opportunity to think carefully about why they rejected other economic and political systems.

Stockdale isn’t the only heroic figure who learned from and admired philosophy. Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. said that his favorite book after the Bible was Plato’s Republic: “it brings together more of the insights of history than any other book. There is not a creative idea extant that is not discussed, in some way, in this work. Whatever realm of theology or philosophy is one’s interest—and I am deeply interested in both—somewhere along the way, in this book you will find the matter explored.” The influence of Plato’s thought is evident in King’s own philosophy. In his historic “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” King invokes Plato’s famous “allegory of the cave” (from the Republic) in order to justify taking actions (like civil disobedience) that were contrary to the conventional values of his era:

Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half-truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, we must see the need of having nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men to rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood.

In other writings, King makes reference to moral lessons he learned from Plato’s dialogues the Symposium and Phaedrus.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was a Protestant minister, yet some people mistakenly think that there is a conflict between being religious and studying philosophy. St. Paul did say, “Beware lest any man spoil you through philosophy and vain deceit” (Colossians 2:8), but most Christians historically have taken this to mean only that philosophy—if practiced in a shallow or specious way—can be destructive of faith, not that it must be, or must be avoided intrinsically. Francis Bacon (1561–1626), whose works were a major influence on empiricist philosophy of science, stated, “It is true that a little philosophy inclineth man’s mind to atheism; but depth in philosophy bringeth men’s minds about to religion.” The plausibility of Bacon’s claim is reflected in the impressive list of seminal philosophers who were theists (including Plato, Aristotle, Descartes, Leibniz, Spinoza, Berkeley, and Kierkegaard). Not only do many great philosophers believe in God, but they have also influenced the development of organized religion. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam — often referred to as “the Abrahamic religions” — originally developed independently of philosophy, but the self-understanding and intellectual content of these religions was shaped by philosophers. The philosopher-theologian Maimonides synthesized Judaism with the philosophy of the pagans Plato and Aristotle, and Averroes and Avicenna did the same for Islam. Saint Augustine had a lasting impact on Christianity by interpreting the Bible in the light of Plato’s philosophy, and a few centuries later Saint Thomas Aquinas re-interpreted Christianity using the thought of Aristotle. Of course, not all Christians agree that the influence of philosophy has been a good thing. Martin Luther, who started the Protestant Reformation, famously said, “Philosophy is the Devil’s whore,” meaning that the influence of pagan philosophy had corrupted Christianity. However, ironically, Martin Luther’s own understanding of Christianity was deeply influenced by Augustine. Whatever stance you take, it seems clear that, if Christians, Jews, and other theists refuse to learn about philosophy, it is due to laziness, not a matter of principle.

3. Philosophy and Science

Philosophy did not only have a significant impact on religion, though. Modern natural science arose from philosophy. This is reflected in the fact that, if you get a doctorate in any science — including physics, biology, chemistry, or mathematics — it’s a PhD, which is an abbreviation of the Latin for “Doctor of Philosophy.” The ancient pre-Socratic philosophers were the first to experiment and speculate about the physical world and provide naturalistic explanations for phenomena, setting the stage for all later science. Anaxagoras (fifth century BCE) correctly surmised that the Sun was not a god but actually a “hot stone” much larger than it appeared, that the Moon only shined because of light reflected from the Sun, and that eclipses were caused when objects came between the Earth and the Sun. Leucippus (fifth century BCE) and Democritus (460–370 BCE) developed the first version of the atomic theory, which was later confirmed by chemist John Dalton (1766–1844 CE). Galileo (1564–1642) was inspired by his reading of Plato to mathematize physical motion. Even computers, the most revolutionary scientific achievement of our era, are a gift of the philosophers. (You’re welcome!) Binary arithmetic, which is the basis of all computers, was invented by philosopher G. W. Leibniz.

Leibniz had several acrimonious debates with Isaac Newton. One thing they quarreled over was who discovered calculus. The answer is that Newton discovered it first in time, but Leibniz announced his discovery first, and we use Leibniz’s symbolism for the calculus nowadays. They also argued over whether location in space is relative or absolute. Newton argued that space and time were absolute, but Einstein would later prove Leibniz right about the relativity of space and time. It’s tempting for the humanist to crow that the philosopher won that argument. However, Newton described himself as a “natural philosopher,” and he would have been genuinely offended at the suggestion that he was not really a philosopher. Of course, most scientists nowadays are not philosophers. As Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) explained, this is because, once we know the proper methodology for solving problems on a certain subject, “this subject ceases to be called philosophy, and becomes a separate science.” Only the questions “to which, at present, no definite answer can be given remain to form the residue which is called philosophy.” So over time there is an increasingly smaller sphere of purely philosophical questions. Does this mean that science could completely replace philosophy?

No.

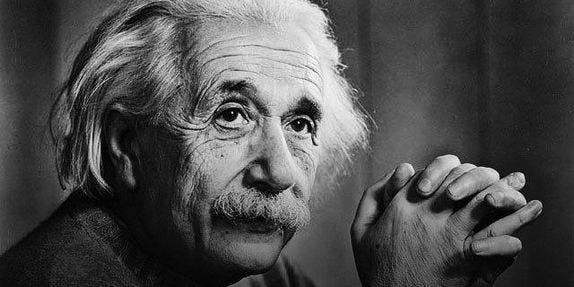

There are at least three reasons why it is impossible that all of philosophy will be replaced by natural science, or that philosophy will become obsolete. First, the history of science alternates between long periods of “normal science” and brief periods of “revolutionary science.” During periods of normal science, scientists largely agree about the way the world works and the proper methodology for studying it. Normal science is an impressive activity, and those who do it deserve our utmost respect and admiration. However, revolutionary science is what the true geniuses of science do: people like Aristotle, Galileo, Newton, John Dalton, Darwin, Erwin Schrödinger, and Einstein. During scientific revolutions, scientists realize that their previous worldview and methodology do not do justice to some aspect of reality. Consequently, they have to radically restructure their concepts. For example, Einstein had to fundamentally rethink what space, time, and gravity were in order to formulate the Special and General Theories of Relativity. During periods of scientific revolution, scientists become philosophers, and draw on the work of other philosophers to help inform their views (for example, Galileo was influenced by Plato, Dalton drew on Democritus, and Einstein said that his approach to science was shaped by philosopher David Hume). Consequently, when another scientist asked him about the importance of physicists learning about philosophy, Einstein replied:

I fully agree with you about the significance and educational value of methodology as well as history and philosophy of science. So many people today—and even professional scientists—seem to me like somebody who has seen thousands of trees but has never seen a forest. A knowledge of the historic and philosophical background gives that kind of independence from prejudices of his generation from which most scientists are suffering. This independence created by philosophical insight is—in my opinion—the mark of distinction between a mere artisan or specialist and a real seeker after truth.

The second reason that natural science will never replace philosophy is that sciences like physics are successful precisely because they limit their inquiry to particular aspects of reality using particular methods. If someone argues that there is nothing to reality besides what is studied by physics, we can legitimately ask her why she thinks this. However, the answer to the question of whether there is anything beyond physics cannot be provided from within physics. Physics uses scientific methods to study reality insofar as it is physical. But the question we are asking is whether there is a reality that is not physical. Since the methodology of science is what we use to study reality only insofar as it is physical, we cannot use that same methodology to explore whether there is anything that is not physical. More generally, you cannot show from within the limits of something that there is nothing outside that limit. You have to straddle a limit, conceptually speaking, in order to define it. So if you try to show that there is nothing beyond the factual and methodological limits of physics, you have already transcended the limits of physics.

Erwin Schrödinger won the Nobel Prize in physics as one of the founders of quantum mechanics. (Schrödinger was also a noted cat lover/hater.) Yet he stressed the limitations of science when he said that

the scientific picture of the real world around me is deficient. It gives a lot of factual information, puts all our experience in a magnificently consistent order, but it is ghastly silent about all and sundry that is really near to our heart, that really matters to us. It cannot tell us a word about red and blue, bitter and sweet, physical pain and physical delight; it knows nothing of beautiful and ugly, good or bad, God and eternity. Science sometimes pretends to answer questions in these domains, but the answers are very often so silly that we are not inclined to take them seriously.

The final reason that philosophy will never be obsolete is that it includes ethics, political philosophy, and philosophical theology. These topics are intrinsically controversial but also inescapable. As I am fond of telling my students, whatever opinions you have in these areas have their origins, at least in part, in philosophical thought. Do you think that the purpose of life is to make the most out of your intelligence and contribute to your community? You’re an Aristotelian. Do you think that there is no purpose to life except for the one each of us chooses for herself? You’re an existentialist, like Sartre, Camus, or Beauvoir. Do you think that morality has to be explained psychologically, by our emotions and other motivations? You’re a Humean. Do you think that what is right is to do whatever produces the greatest happiness of the greatest number of people? You’re a utilitarian, like Bentham and Mill. Do you think that there are some actions that are intrinsically wrong and must never be done, even if they would result in desirable consequences? You’re a Kantian. Do you think that government is designed to protect our inalienable rights to life, liberty, and property? You’re a Lockean. Do you think that government must protect our freedoms, but wealth inequality is justifiable only insofar as it benefits those most in need? You’re a Rawlsian. Do you think that much of religious belief can be justified by philosophy? Please say hello to my friend Thomas Aquinas. Do you think we can legitimately have religious belief even though most of it must be accepted on faith? Go hang out with my buddies Pascal, Kierkegaard, and William James. Do you believe that religion is superstition that has had a largely negative influence on the world? Read Bertrand Russell or J. L. Mackie. Or do you dismiss philosophy as nothing but rationalizations for the will to power, or our basic drives for reproduction and destruction, or socio-economic structures of domination? Enjoy Nietzsche, Marx, Freud, and Foucault. (Oops! They’re philosophers too!) The question is not whether philosophy is important to you. It already is. The only question is whether you choose to become self-aware and critically reflective about the philosophical beliefs that you hold.

John Maynard Keynes, one of the most influential economists of the twentieth century, made a similar point:

The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back. I am sure that the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas.

4. Conclusion

We have seen that philosophy is a valuable part of vocational training for many careers. Beyond that, philosophy is important to the maintenance of democracy itself: those who have been trained to argue rationally and constructively have learned to value discussion over violence, and pluralism over intolerance. Finally, philosophy is responsible for so much that we view as valuable in Western civilization, from natural science to the various formulations we use to talk about ethics, politics, and spirituality. For all these reasons, the anti-intellectualism that delights in degrading philosophy is both unwarranted and unfortunate.

I will conclude with a brief quotation about the value of philosophy by John Cleese. Cleese, who obtained a law degree from Cambridge University before becoming one of the founders of the legendary comedy troupe Monty Python, said:

Philosophy seems so harmless, and yet, among dictatorships, philosophers have always been among the first people to be silenced. Why have dictators bothered to silence philosophers? Maybe because ideas really matter: they can transform human lives.

I invite you to review the quotations above from Jefferson and King, from Einstein and Schrödinger, from Hampshire and Stockdale, from Keynes and Cleese, and then ask yourself: can you afford not to study philosophy?

This essay was originally presented as a talk at the University of Alabama in Huntsville on 21 March 2023, and is adapted from Bryan W. Van Norden, Taking Back Philosophy: A Multicultural Manifesto (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), Chapter 4: “Welders and Philosophers.”

Bryan W. Van Norden is James Monroe Taylor Chair in Philosophy at Vassar College, and the author of ten books, including Taking Back Philosophy: A Multicultural Manifesto. Opinions expressed here are his own and may not reflect those of Vassar College.