I was an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania from 1981 to 1985. I majored in philosophy, but I was only one course short of a second major in what we then called “Oriental Studies.” Penn’s Department of Oriental Studies was very different from its current Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, and not only in name.1 When I was an undergraduate, Penn offered only three years of modern Chinese (and only Mandarin Chinese) and one year of classical Chinese. There were two sections of “first-year, intensive Mandarin Chinese,” but it still was sufficiently rare for students to study Chinese (especially white guys like me) that others were often incredulous if you told them. I remember that during the first day of second-year Chinese, the professor teaching the course (the genial A. Ronald Walton, who passed away in 1996) was welcoming us back from summer break and lecturing about some of the things we would cover in the coming year. About fifteen minutes into the lecture, a student put up his hand and said, “Sorry, is this course introductory microeconomics?”

Professor Walton answered, “No, this is second-year Mandarin Chinese,” and continued with his lecture.

The student sat there for another five minutes, before raising his hand again and saying, “No, seriously. What is this course?”

The student apparently thought it was so unbelievable that they were in a course on Mandarin Chinese that they assumed the professor was joking, but Professor Walton gently explained, “This is really a course in Mandarin Chinese!” and the student finally left.

I used to joke that the only people who studied Chinese back then were linguists, missionaries, and spies. In fact, our first-year textbook2 included the following sample dialogue between an American student and one of his Chinese hosts:

Chinese Host: Yuyan xue shi shenme 語言學是什麼?(“What is linguistics?”)

American Student: Yuyan xue shi yong kexue de fangfa yanjiu yuyan 語言學是用科學的方法研究語言。(“Linguistics is the use of scientific methods to study language.”)

In the forty years since I learned those phrases, I have never had occasion to use them. I forget who wrote our second-year Chinese textbook, but I remember that it included a lesson explaining the Parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11–32). In addition, I once dated a woman who was so surprised that I knew Chinese that she sincerely asked me, “Are you a spy?”

I replied, “No, but if I were a spy I couldn’t tell you,” and then I winked at her.

The author of our first-year textbook, John DeFrancis, had no special connection with Penn, but he had had an interesting career. During the “Red Scare” in the US during the McCarthy era of the early 1950s, DeFrancis bravely spoke up in defense of an innocent colleague falsely accused of being a traitor, and as a result was blacklisted from American academic jobs for over a decade. Fortunately, he eventually returned to academia and became a leading figure in Chinese-language education. I still recommend his book, The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1986), for its incisive rejection of the myth that Chinese characters are all just “ideograms” or “pictograms.”

Mainframe computers were around when I was an undergraduate (I’m not that old!), but desktop computers were rare, and laptops, cell phones, and the internet were still science fiction. To learn Chinese characters back then, we were given sheets with columns of squares and required to write out each new character at least twenty times. In addition, we learned how to look up characters in traditional dictionaries by their bushou 部首 (radicals). For listening practice, we had to go physically to the language lab (then located in the basement of Logan Hall). Lessons were recorded on open-reel tapes (the predecessor to cassette tapes), which were stored in one room. We would sign them out and then take them to the next room, where there were rows of reel-to-reel tape players with headsets.

Penn’s only course on classical Chinese at that time was taught by Nathan Sivin (1931–2022), who was also a distinguished expert on the development of Chinese science. (Sivin told me that, while re-creating recipes in a book of ancient alchemy so that he could chemically analyze the results, he had accidentally destroyed an oven in the chemistry lab at MIT, when the “Daoist immortality elixir” he was heating exploded.) Our textbook was the three-volume A First Course in Literary Chinese, which is an authoritative, but not very reader-friendly, guide.3 One of my classmates was almost reduced to tears by the complexity of its grammatical explanations. Still, I (and the other four students in the course) got a great foundation in classical Chinese.

I also took a course on traditional Chinese law, taught by Allyn Rickett. Rickett and his wife Adele had become famous for their book, Prisoners of Liberation,4 which told the story of the four years they spent in a Chinese prison after being convicted of spying at the start of the Korean War. (Like many people in his generation, Rickett first learned Japanese in the Army in World War II, and he had interrogated Japanese soldiers. He remarked that this gave him added appreciation for the technique of his own interrogator. He also quipped, “Nothing is better for your command of vernacular Chinese than being interrogated for four years in a Chinese prison.”) Because they admitted that the Chinese had a right to arrest them for spying (they were reporting Chinese troop movements to the US Embassy), Allyn and Adele were accused of having been “brainwashed” upon their return to the US. I still assign my students the section of their book in which the Ricketts describe the atmosphere in Beijing as Chinese read the American newspapers that were openly calling on the US to invade China after they drove the North Korean army to the Yalu River. This puts a very different spin on China’s “surprise attack” on UN forces.

Then, as now, much of the actual language instruction at Penn was done by hardworking and dedicated native speakers. My instructor in first-year intensive Mandarin Chinese was a kind and enthusiastic graduate student, Liang Zhuzhu. Eugene Liu (1937–2018), a genial Chinese gentleman, was my instructor in the first semester of second-year Chinese. Perhaps the best native-language instructor I ever had was Zhang Taitai 張太太 (Mrs. Zhang), who did a terrific job of teaching the second semester of second-year Chinese and was loved by all her students.5

Kung-fu films (usually recorded in Cantonese and then badly dubbed into English) were very popular in the US after the international success of Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon (Longzheng hudou 龍爭虎鬥; 1973), but it was rare to be able to watch films with spoken Mandarin Chinese. I remember that a group of us eagerly attended a special screening of a feature-length film in Mandarin about the heroic struggles of the Chinese People’s Women’s Olympic Volleyball Team. (Really.) But one of the high points of my junior year was a screening of the classic film Aile zhongnian 哀樂中年 (The joys and sorrows of middle age; 1949). (The original screenplay was written by the great Eileen Chang. I later wrote the first version of the Wikipedia article on this film. The current version is here.) This film was screened in Oriental Studies 470: Third-Year Chinese, a course taught by a young, charismatic, and impressively tall professor: Victor H. Mair.

There were only five students in this class (one of whom dropped out of college during the course—I assume not because of Chinese). The syllabus featured readings by great twentieth-century Chinese authors like Lu Xun 鲁迅. I have often said that, even if I never used Chinese in my career again, the years I spent studying it would still have been worth it because that is how I first encountered the powerful writings of Lu Xun.6 Introducing me to Lu Xun is just one of the intellectual debts I owe to Victor. I still have fond and vivid memories of his course, almost forty years later. Victor’s boundless enthusiasm was infectious, and his encyclopedic knowledge was impressive. (He once casually quoted the Middle English phrase “ayenbite of inwyt” to help explain an expression in Chinese.) Although I enjoyed the course and learned a lot, I was not an especially diligent student. My transcript shows I earned a B for both semesters (which I am sure was a generous grade).

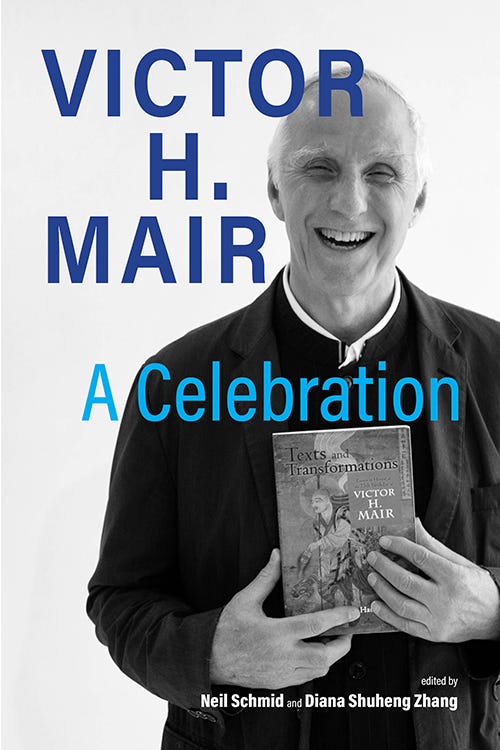

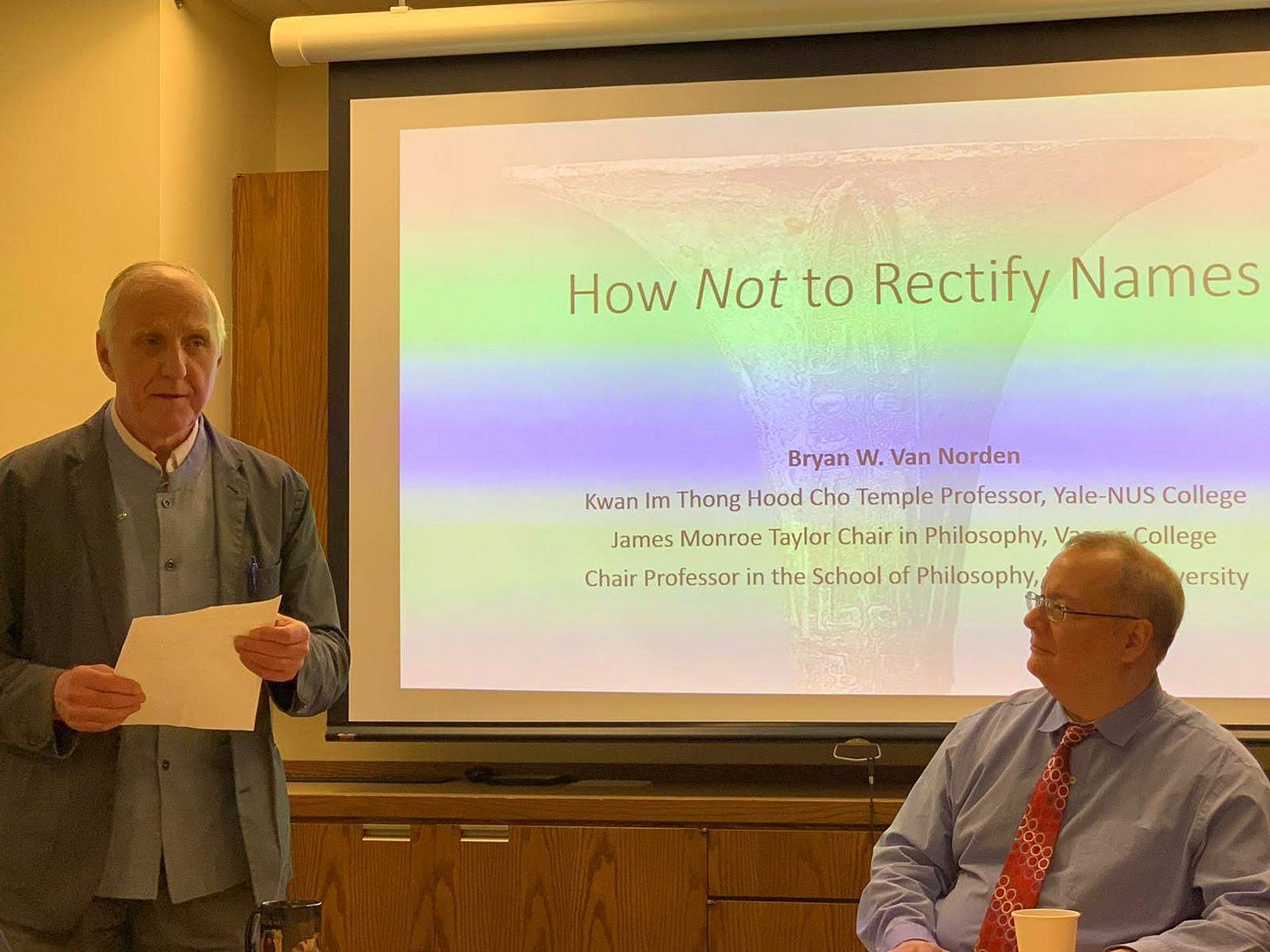

After Penn, I went on to get a PhD in Philosophy from Stanford and became a professor myself. Along the way, I became increasingly aware of what an impressive scholar Victor really is, with substantial contributions in translation, linguistics, and archaeology. In addition, his articles about vernacular Chinese on Penn’s Language Log (https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/) are a delight. A few years ago, I was Victor’s guest at Penn, where I give a talk on the famous passage in the Analects in which Confucius shouts at his disciple, Zeng Shen 曾參, “My Way is bound together by one thing!” Zeng assents enthusiastically, Confucius leaves the room, and the other disciples rush up to ask Zeng what Confucius meant. Zeng explains that “The Way of the Master is loyalty and reciprocity, and that is all.” So many aspects of this story are puzzling, including the fact that Zeng explains the “one” thing referred to by Confucius by mentioning two virtues. In my talk, I argued that the interpretation of the passage offered by the “orthodox” commentator Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200) is implicitly modeled on a kōan / gong’an 公案 exchange, in which a master tosses a cryptic comment at a disciple, the disciple is shocked into enlightenment, and the disciple then becomes a master in his own right, who can use upāya, skillful means, to paraphrase the teachings in a way useful to the unenlightened.7 Victor exclaimed, “I never understood that passage until now!” and he ostentatiously bowed in front of me.

I may have “enlightened” my teacher (pretty good for a B student!), but I am sure I will never be revered as much as Master Zeng. However, as this volume attests, “Master Mair” will live forever in not only the fond memories of his students but also the endless reverberations of his influential teaching and research.

Mei jiaoshou wansui! Wan wansui! 梅教授万岁!万万岁!

This essay was originally published in Neil Schmid and Diana Shuheng Zhang, eds., Victor H. Mair: A Celebration (Cambria, 2023).

Bryan W. Van Norden is James Monroe Taylor Chair in Philosophy at Vassar College, and the author of ten books, including Taking Back Philosophy: A Multicultural Manifesto. Opinions expressed here are his own and may not reflect those of Vassar College.

The name change was due, in part, to Edward Said’s seminal work, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1979).

John DeFrancis and Yung Teng Chia-yee, Beginning Chinese, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976).

Harold Shadick and Ch’iao Chen 喬健, A First Course in Literary Chinese, 3 vols. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1968). Since then, I have written my own textbook, which aims to be more reader-friendly: Classical Chinese for Everyone: A Guide for Absolute Beginners (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2019).

Allyn and Adele Rickett, Prisoners of Liberation (New York: Anchor Books, 1973).

I think this was Victor Mair’s late wife, Li-ching Chang 张立青 [1936-2010]. For more on her, see “Li-ching Chang, 1936-2010,” The Blog of Pinyin.info, http://pinyin.info/news/2010/li-ching-chang-1936-2010/.

See Bryan Van Norden, “The Sanity of Insanity: Lu Xun’s ‘Diary of a Madman,’” in Fangfang Ding, Jing Hu, et al. eds., Appreciating Modern Chinese Literature Classics (Nanjing: Nanjing University Chubanshe, forthcoming), and Bryan Van Norden, Lee Moore, and Rob Moore, “Kong Yiji 孔乙己,” recorded February 5, 2022 on Chinese Literature Podcast, audio, 35:16, https://www.chineseliteraturepodcast.com/?p=1097.

Bryan Van Norden, “Unweaving the ‘One Thread’ of Analects 4:15,” in Confucius and the “Analects”: New Essays, ed. Bryan Van Norden (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 216-36.

Thank you so much for this great piece.